How Market Timing Affects Portfolios

This is a follow-up to my post last October entitled “Should You Increase Equity Allocation in Retirement?” (https://www.cognizantwealth.com/2013/10/24/should-you-increase-equity-allocation-in-retirement/). At that time I cited research by Pfau & Kitces suggesting that retirees begin their retirement with their investment portfolio allocated very conservatively, and then gradually increase the allocation to stocks as they age. In this post I’ll discuss some additional research by Craig Israelsen, an executive in residence at the Woodbury School of Business at Utah Valley University, which further explains the rationale behind this counter-intuitive approach to investing.

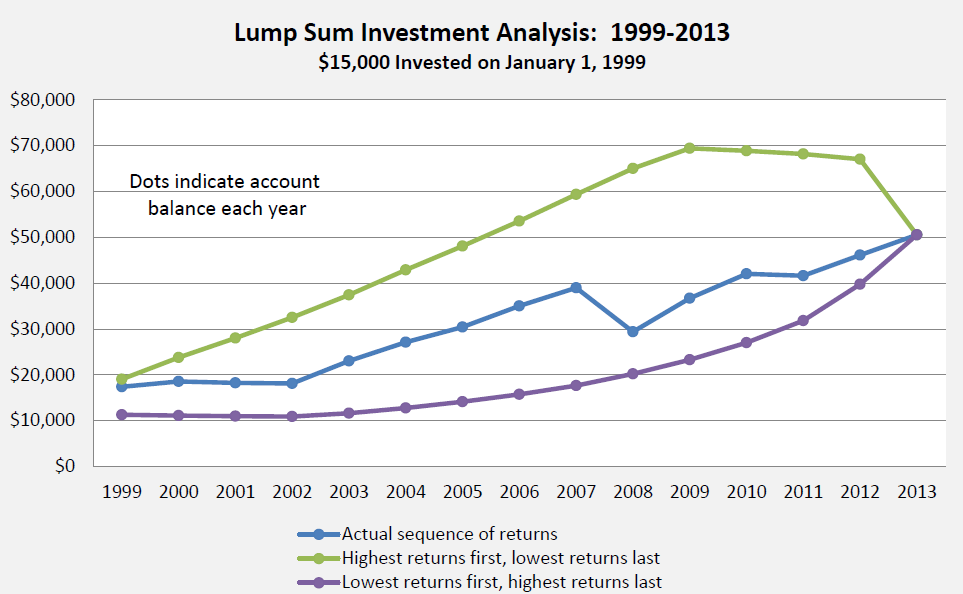

It all has to do with the way the sequence of returns affects an investment portfolio. First, let’s start with a portfolio in which a single lump sum investment of $15,000 is made at the beginning of 1999. The chart below shows the value of this portfolio – which is allocated across 12 different asset classes for diversification – at the end of each year over a 15 year period. The blue line represents the actual returns over this period. The green line sorts the returns such that the highest annual return occurs first, followed by the second highest, and so on, with the lowest return occurring in the last year. The purple line is just the opposite; the lowest return occurs in the first year and the highest return occurs in the last year.

Perhaps surprisingly, you can see that for a single lump sum investment, the sequence of returns does not matter. The ending value of the portfolio always turns out the same regardless.

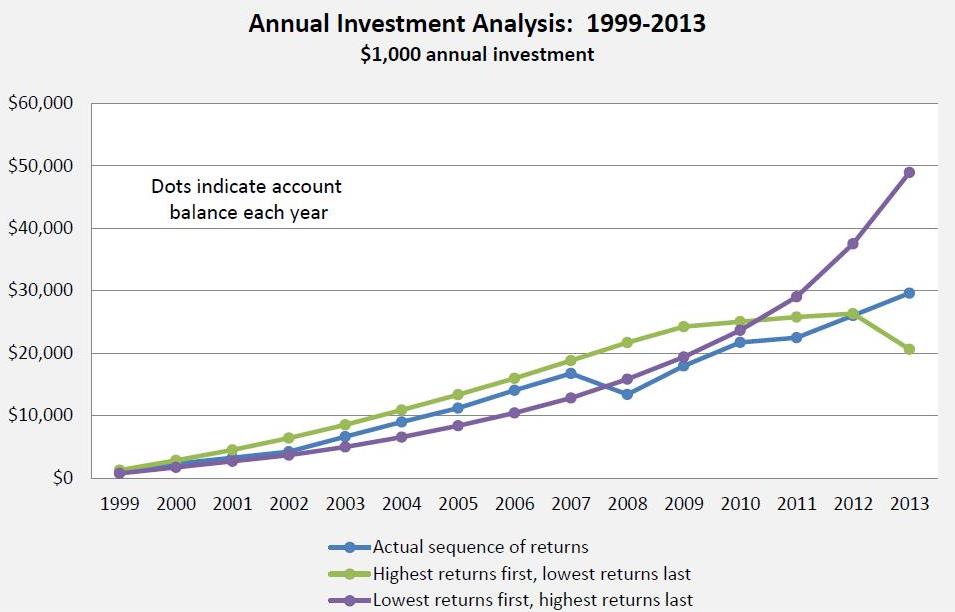

However, what if you were to invest $1000 per year over the same period rather than $15,000 up front? As you can see from the following graph, the sequence of returns now has a pretty big impact:

In this case, the sequence where the lowest returns come first and the highest come last provides a significantly greater return than either of the other two. This can be understood intuitively. In the early years the portfolio size is relatively small, so the returns don’t have as much effect on portfolio growth as compared to the later years after most of the contributions have been made and the portfolio is bigger.

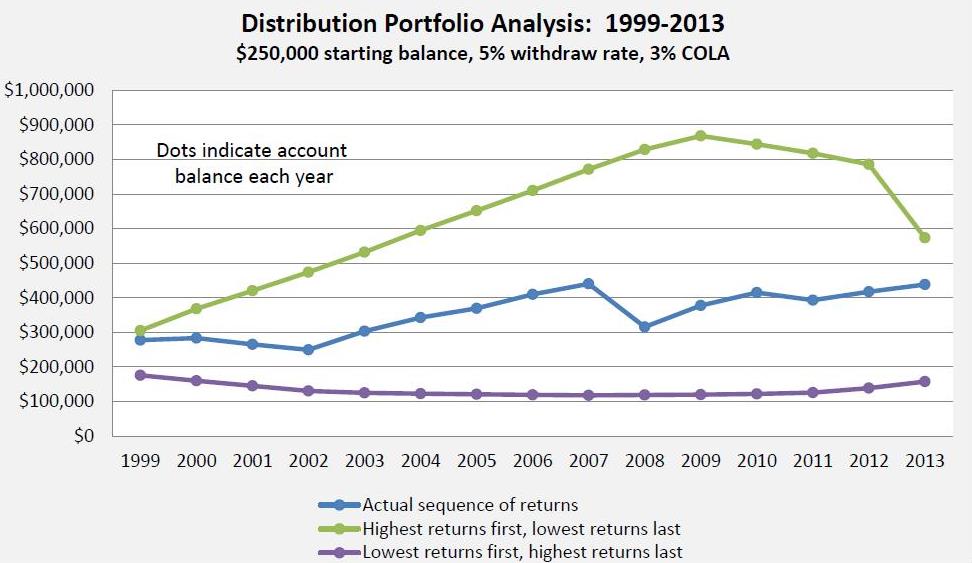

So far we’ve been talking about accumulating a portfolio. What about the period of time after retirement when you will be withdrawing from it? Here’s a graph showing the growth & decline of a $250K portfolio with a 5% annual withdrawal rate that increases by 3% each year (to take into account inflation) over the same period. As above, the blue, green, and purple lines represent their same respective sequences of returns.

In this case, consistent with the research from Pfau & Kitces, the worst scenario is the one where the early returns are the lowest. And the difference is again significant. When the good returns occurred early in retirement, the ending portfolio balance ended up a bit higher than $438,000. But in the reverse case, it tumbled to less than $160,000.

Since we don’t know in advance which will be the good years and which will be the bad ones, what is the best approach to follow when saving for retirement? Based on this research, you would most likely start with a moderately conservative allocation model when you’re in your twenties (or whenever you are able to begin saving money). You would then increase your allocation to higher-performing asset classes such as stocks as your savings grow, possibly maximizing your expected returns (and risk) when you’re in your forties. Sometime around ten or so years prior to retirement you would begin to dial down the risk (and consequent returns), so that by the time you are within five years of retirement your portfolio would be approaching its most conservative allocation. (Although Israelsen’s research suggests that this is the time to maximize your returns, it’s also one of the most important times to avoid big losses. I’d suggest opting for the latter over the former). You’d probably keep your portfolio allocation very conservative for the first five or ten years after retirement, at which point you would start increasing your exposure to riskier assets once again.

How conservative or aggressive you need to make your portfolio during these transition periods depends on two factors: how much you need to grow your savings in order to enjoy the retirement you want, and how tolerant you are about risk and about losses.

Once you’ve got your allocation model defined, you will then have to select from a myriad number of mutual funds or ETFs to build your portfolio. Unfortunately for those of you looking for a simple do-it-yourself solution, I have not found one target date fund (those mutual funds found in many 401(k) plans that automatically change allocations based on your age) that even comes close to following a glide path similar to the approach above.

We can’t control the sequence of returns, but we can control the risk level of a portfolio during periods of time in which it is particularly sensitive to losses. A flexible asset allocation model is one more tool we can utilize to help deal with future uncertainty.